A fourth ransomware campaign focused on Ukraine has surfaced today,

following some of the patterns seen in past ransomware campaigns that

have been aimed at the country, such as XData, PScrypt, and the infamous NotPetya.

The ransomware was discovered today by a security researcher who goes online only by the name of MalwareHunter.

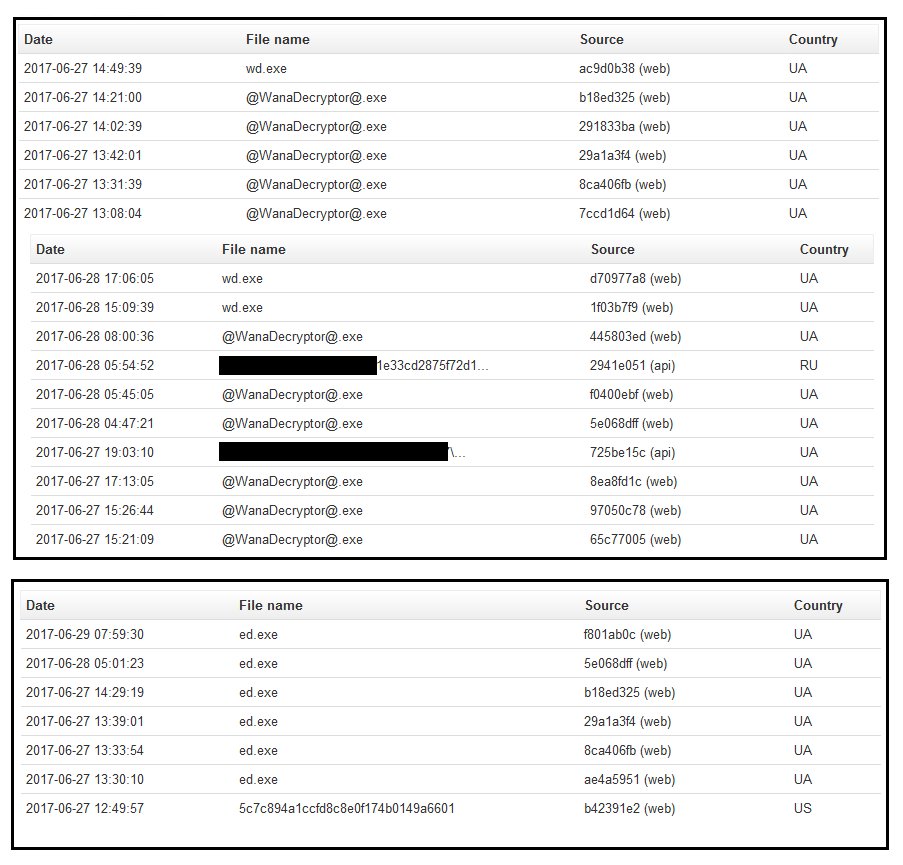

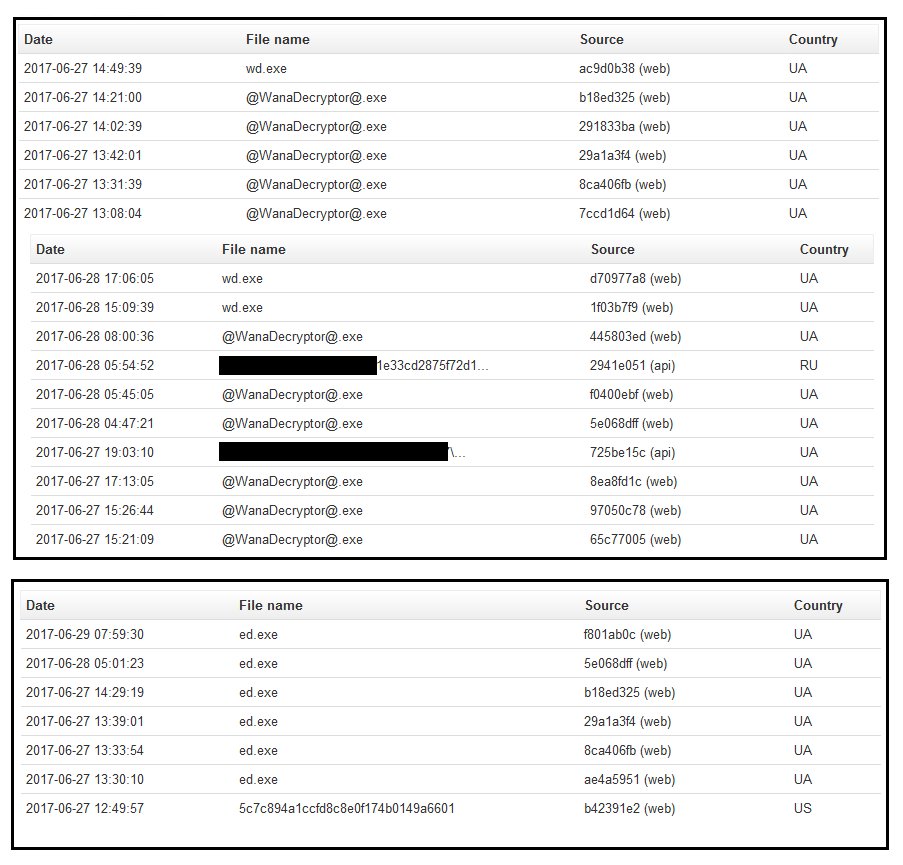

The researcher says the ransomware got his attention because mostly Ukrainian victims were submitting samples for analysis on VirusTotal.

In the past month and a half, Ukraine has been bombarded with ransomware campaigns. The first was

XData (mid-May), the second was PSCrypt (last week), and then NotPetya (started on Tuesday).

According to the researcher, this fourth ransomware campaign started on Monday, one day before NotPetya, and piqued his interest because of several reasons.

This file path is specific to M.E.Doc IS-pro, a software application used for accounting in Ukraine. Both XData and the NotPetya ransomware outbreaks used the update servers of M.E.Doc to deliver their ransomware payloads. Microsoft, Kaspresky, Cisco, and other cyber-security companies have specifically pinpointed M.E.Doc software update servers as the source of the NotPetya outbreak.

It is unclear if this recently discovered ransomware reached users via a trojanized update from the same server or a trojanized M.E.Doc app installed from scratch.

Since the start of the NotPetya ransomware outbreak that affected countries all over the world, M.E.Doc has consistently denied that it ever hosted trojanized versions of its apps.

On Facebook, M.E.Doc says it enlisted the help of Cisco experts to clear its name and investigate what really happened on its servers. In an email to Bleeping Computer, the company also said it invited officers from the Department of Cyber Police to also investigate what happened.

While Cisco and Ukrainian authorities are looking into identifying the real culprit behind the M.E.Doc server hijacking, it's now becoming clear that there might be another ransomware that used the same server to infect victims, albeit with less successful results than NotPetya.

MalwareHunter says this ransomware was "designed" to look like WannaCry, but it's not an actual clone. For starters, the ransomware is coded in .NET, while the original WannaCry was coded in C.

The WannaCry lookalike doesn't use any NSA exploits to spread laterally, and its internal structure is also different. The only thing it shares with the original WannaCry it's its GUI that shows the countdown timer and the ransom demand.

In most cases, .NET-based ransomware is usually a sign that the author has no coding experience. This is not the case with this WannaCry lookalike.

"The WannaCry lookalike is probably one of the best .NET ransomware strains we've seen," MalwareHunter says, "surely no skids made this."

The ransomware infects systems via an initial dropper that unpacks and saves two files locally, the GUI for the WannaCry-like window, and the encrypter component.

The ransomware uses a Tor-based command and control server, won't start without special command-line arguments, and will kill processes before encrypting files used in live apps. This last feature, MalwareHunter says is unique for all ransomware families he analyzed.

The same thing was noticed with XData — based on stolen AES-NI codebase; PSCrypt — based on GlobeImposter; and NotPetya — disguised as Petya.

Ransomware operators trying to pass as famous threats ain't anything new, but AES-NI and GlobeImposter are very small enterprises. There's hardly a reason for anyone to imitate these two unless wanting to go under the radar as a very very ordinary operation.

Slowly, it's becoming somewhat clear that someone is slinging ransomware specifically at Ukraine and is trying to pass as a mundane cyber crime operation, hiding other motives.

Putting all clues together, we see four ransomware campaigns that have targeted Ukraine, have tried to pass as other ransomware threats, have quality code, and three of which appear to have used the same server to spread.

There is no clear-cut evidence that the same person or group is behind all campaigns, but there are too many coincidences to ignore.

GUI: 7b6a2cbb8909616fe035740395d07ea7d5c2c0b9ff2111ae813f11141ad77ead

Encrypter: db8e7098c2bacad6ce696f3791d8a5b75d7b3cdb0a88da6e82acb28ee699175e

The ransomware was discovered today by a security researcher who goes online only by the name of MalwareHunter.

The researcher says the ransomware got his attention because mostly Ukrainian victims were submitting samples for analysis on VirusTotal.

In the past month and a half, Ukraine has been bombarded with ransomware campaigns. The first was

XData (mid-May), the second was PSCrypt (last week), and then NotPetya (started on Tuesday).

According to the researcher, this fourth ransomware campaign started on Monday, one day before NotPetya, and piqued his interest because of several reasons.

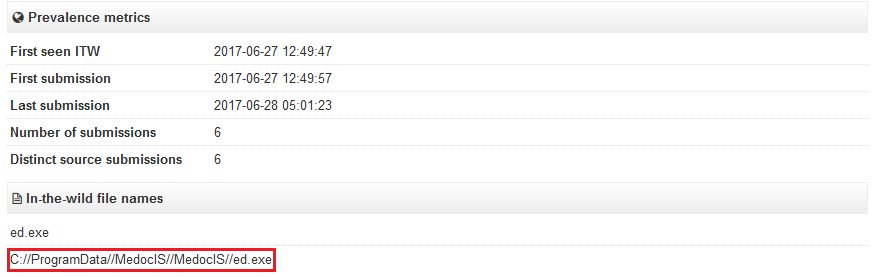

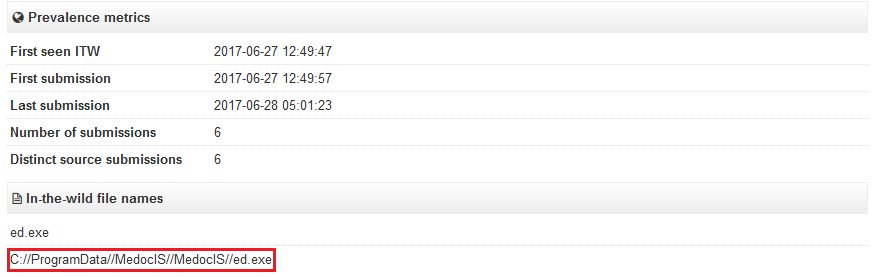

M.E.Doc servers appear to have distributed another ransomware

The one clue that stood out was the location of the ransomware's component, which was: "C://ProgramData//MedocIS//MedocIS//ed.exe"

This file path is specific to M.E.Doc IS-pro, a software application used for accounting in Ukraine. Both XData and the NotPetya ransomware outbreaks used the update servers of M.E.Doc to deliver their ransomware payloads. Microsoft, Kaspresky, Cisco, and other cyber-security companies have specifically pinpointed M.E.Doc software update servers as the source of the NotPetya outbreak.

It is unclear if this recently discovered ransomware reached users via a trojanized update from the same server or a trojanized M.E.Doc app installed from scratch.

Since the start of the NotPetya ransomware outbreak that affected countries all over the world, M.E.Doc has consistently denied that it ever hosted trojanized versions of its apps.

On Facebook, M.E.Doc says it enlisted the help of Cisco experts to clear its name and investigate what really happened on its servers. In an email to Bleeping Computer, the company also said it invited officers from the Department of Cyber Police to also investigate what happened.

While Cisco and Ukrainian authorities are looking into identifying the real culprit behind the M.E.Doc server hijacking, it's now becoming clear that there might be another ransomware that used the same server to infect victims, albeit with less successful results than NotPetya.

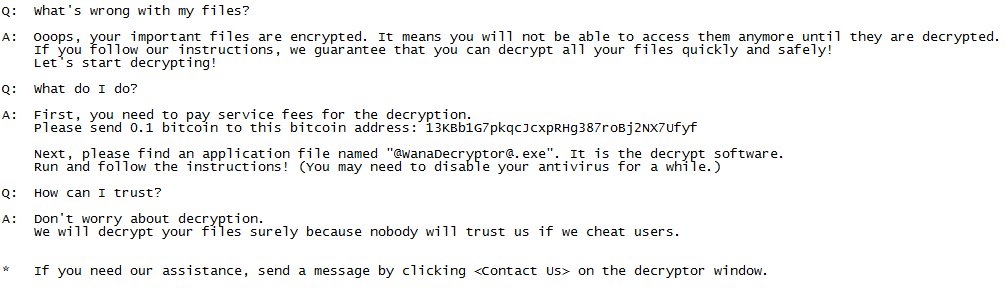

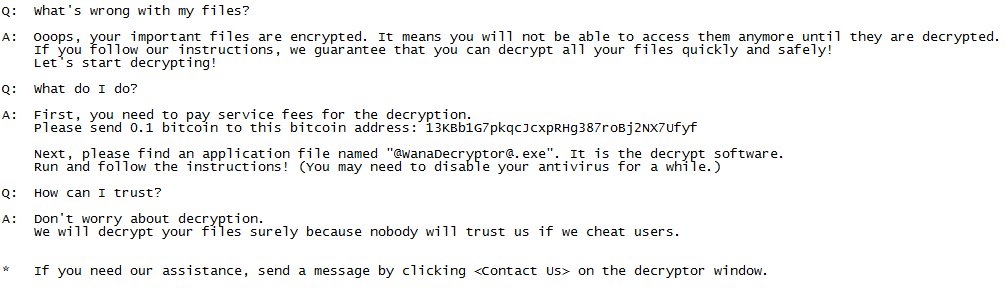

"Designed" to look like WannaCry, but nothing more

This "fourth" ransomware is designed to look like WannaCry, the ransomware that affected tens of thousands of computers in mid-May.MalwareHunter says this ransomware was "designed" to look like WannaCry, but it's not an actual clone. For starters, the ransomware is coded in .NET, while the original WannaCry was coded in C.

The WannaCry lookalike doesn't use any NSA exploits to spread laterally, and its internal structure is also different. The only thing it shares with the original WannaCry it's its GUI that shows the countdown timer and the ransom demand.

In most cases, .NET-based ransomware is usually a sign that the author has no coding experience. This is not the case with this WannaCry lookalike.

"The WannaCry lookalike is probably one of the best .NET ransomware strains we've seen," MalwareHunter says, "surely no skids made this."

The ransomware infects systems via an initial dropper that unpacks and saves two files locally, the GUI for the WannaCry-like window, and the encrypter component.

The ransomware uses a Tor-based command and control server, won't start without special command-line arguments, and will kill processes before encrypting files used in live apps. This last feature, MalwareHunter says is unique for all ransomware families he analyzed.

Someone is slinging ransomware at Ukraine

What's more peculiar is that this fourth ransomware also fits a pattern observed with the previous strains. This ransomware tries to pass as another family — WannaCry.The same thing was noticed with XData — based on stolen AES-NI codebase; PSCrypt — based on GlobeImposter; and NotPetya — disguised as Petya.

Ransomware operators trying to pass as famous threats ain't anything new, but AES-NI and GlobeImposter are very small enterprises. There's hardly a reason for anyone to imitate these two unless wanting to go under the radar as a very very ordinary operation.

Slowly, it's becoming somewhat clear that someone is slinging ransomware specifically at Ukraine and is trying to pass as a mundane cyber crime operation, hiding other motives.

Putting all clues together, we see four ransomware campaigns that have targeted Ukraine, have tried to pass as other ransomware threats, have quality code, and three of which appear to have used the same server to spread.

There is no clear-cut evidence that the same person or group is behind all campaigns, but there are too many coincidences to ignore.

SHA256 hashes:

Dropper: 51e84accb6d311172acb45b3e7f857a18902265ce1600cfb504c5623c4b612ffGUI: 7b6a2cbb8909616fe035740395d07ea7d5c2c0b9ff2111ae813f11141ad77ead

Encrypter: db8e7098c2bacad6ce696f3791d8a5b75d7b3cdb0a88da6e82acb28ee699175e

Ransom note:

Comments

Post a Comment